Participants

Healthcare providers were recruited for this anonymous online survey through the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research website and social media advertisements. Of 879 participants, 626 (71.2%) were female and 754 (85.8%) were White (Table 2). Mean (SD) age was 45.5 (12.7) years. Registered nurses comprised the largest professional group (n = 223, 25.4%), followed by physicians (n = 156, 17.7%). The most represented physician specialties were psychiatry (n = 42, 26.9%), family medicine (n = 26, 16.7%), and internal medicine (n = 25, 16.0%). A total of 291 participants (33.1%) held prescribing capabilities, 807 (91.8%) currently practiced clinically, and 185 (21.0%) conducted research. Previous psychedelic use was reported by 640 participants (72.8%).

A total of 264 participants (30.0%) reported that they have patients that currently use psilocybin, and 160 (18.2%) reported that they have patients that use MDMA. Most participants reported having seen someone under the influence of psilocybin (n = 650, 73.9%) and MDMA (n = 522, 59.4%) in a recreational context. The majority of these observed experiences were positive for psilocybin (n = 617, 89.8%) and MDMA (n = 457, 79.6%), but negative experiences were also reported for psilocybin (n = 23, 3.3%) and MDMA (n = 54, 9.4%).

Self-reported and objective knowledge

Participants rated how strongly they agreed with statements representing their knowledge and attitudes about the clinical use and legal accessibility of each substance on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). On average, participants rated their self-reported knowledge as highest regarding psilocybin and MDMA therapeutic indications (3.99 and 3.06, respectively), followed by knowledge on risks (3.65, 3.05), and finally on mechanism of action for each substance (3.08, 2.69) (Table 3).

Self-reported knowledge ratings were inconsistent with responses on objective knowledge check items. Respondents scored the lowest on their knowledge of the therapeutic indications of psilocybin and MDMA (20.6% and 2.5%, respectively), despite self-rated knowledge being the highest in this domain. Only 5.5% of respondents answered all 3 knowledge check questions correctly for psilocybin, compared to just 1.1% for MDMA. 35% of respondents answered all 3 questions incorrectly for MDMA, compared to 25.5% for psilocybin.

Respondents scored lower on the MDMA questions compared to psilocybin, consistent with self-rated knowledge. Self-rated and objective knowledge scores were significantly, but weakly correlated (0.26; 95% CI: 0.19, 0.32, p < 0.001 for psilocybin and 0.31; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.37, p < 0.001 for MDMA).

Mean self-rated knowledge of psilocybin was higher on average for physicians compared to other professionals, though this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.13). Mean self-rated knowledge of MDMA was higher for physicians compared to advanced practice providers (APPs) (p = 0.02), nurses (p < 0.001), and mental health professionals (p = 0.02). Compared to other professionals, a greater proportion of physicians responded correctly to at least 2 out of 3 knowledge check questions for both psilocybin and MDMA. This aligns with the higher self-rated knowledge endorsed by physicians relative to other professionals. All professions scored lower on the MDMA knowledge check questions compared to the psilocybin questions.

Primary and trusted sources of knowledge

Popular media (69.5% for psilocybin, 61.8% for MDMA) and academic literature (65.6%, 47.9%) were respondents’ main current sources of knowledge, followed by informal conversations (51.2%, 52.3%) and personal experience (58.7%, 37.8%). Reported sources of knowledge were overall similar for psilocybin and MDMA (Table 3). More respondents learned about psilocybin through academic literature and personal experience, compared to MDMA.

The most trusted sources of knowledge for psilocybin and MDMA were academic research centers (91.0% for psilocybin, 89.4% for MDMA), experienced clinicians or practitioners (90.1%, 92.6%), and professional organizations (76.5%, 76.7%). Only 7.6% and 8.1% of respondents stated they would trust pharmaceutical companies to provide information on psilocybin and MDMA. Responses were overall similar for psilocybin and MDMA.

Attitudes regarding psilocybin and MDMA

Overall internal consistency was high within grouped knowledge and attitude domains, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.73 to 0.91, except for openness to clinical use of psilocybin (0.69) and support for legal access to MDMA (0.51) (Supplemental Table S1).

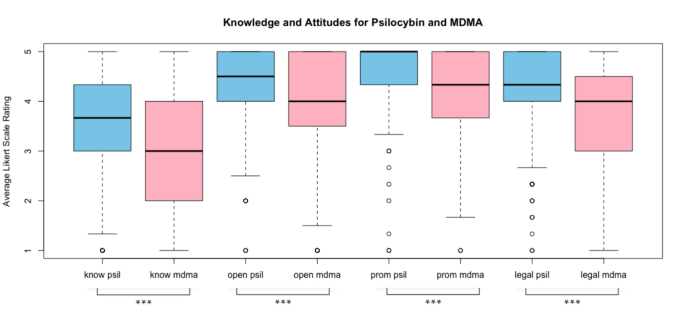

Therapeutic Promise. Belief in therapeutic promise of psilocybin and MDMA was high across all professions (Table 4). Overall, mean (SD) ratings for belief in therapeutic promise were 4.67 [0.53] for psilocybin, and 4.25 [0.73] for MDMA, indicating an average response between “Agree” and “Strongly Agree.” Specifically, 93% believed psilocybin can be delivered safely in clinical settings and 76% felt MDMA could be delivered safely in clinical settings. Similarly, 95% endorsed the therapeutic promise of psilocybin, with 73% endorsing therapeutic benefits of MDMA. Finally, 98% supported further psilocybin research and 92% called for more research on MDMA. Belief in therapeutic promise of psilocybin was significantly higher than for MDMA (p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Openness to Clinical Use. Openness to clinical use was rated a mean of 4.47 [0.69] for psilocybin and 3.98 [0.92] for MDMA. A majority endorsed openness to using psilocybin (89%) and MDMA (67%), and a majority also expressed an interest in further training to use psilocybin (90%) and MDMA (79%) in their practice. Openness to clinical use of psilocybin was lower among physicians compared to other professions. Openness to clinical use of psilocybin was significantly higher than for MDMA (p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Knowledge and attitude ratings for psilocybin and MDMA. Average self-rated knowledge (know), openness to clinical use (open), belief in therapeutic promise (prom), and support for legal access (legal) to psilocybin and MDMA are shown. A 5-point Likert scale rating was used (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Paired t-tests showed that the average rating was significantly higher for psilocybin compared to MDMA across all 4 categories (p-value < 0.001). ***p-value < 0.001 for paired t-test.

Support for Legal Access. 96% of participants supported legal medical use of psilocybin and 84% supported legal medical use of MDMA. Recreational non-medical use had less support with 61% feeling psilocybin should be legally accessible for recreational/non-medical use compared to 36% endorsing the same for MDMA. Finally, 84% noted support for legal access to psilocybin for religious use (not queried regarding MDMA). Mean support for legal access to psilocybin and MDMA (i.e., across all settings) was higher for registered nurses (RNs), mental health professionals (MHPs), and other professionals than for physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs). Support for legal access to psilocybin was significantly greater than for MDMA (p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

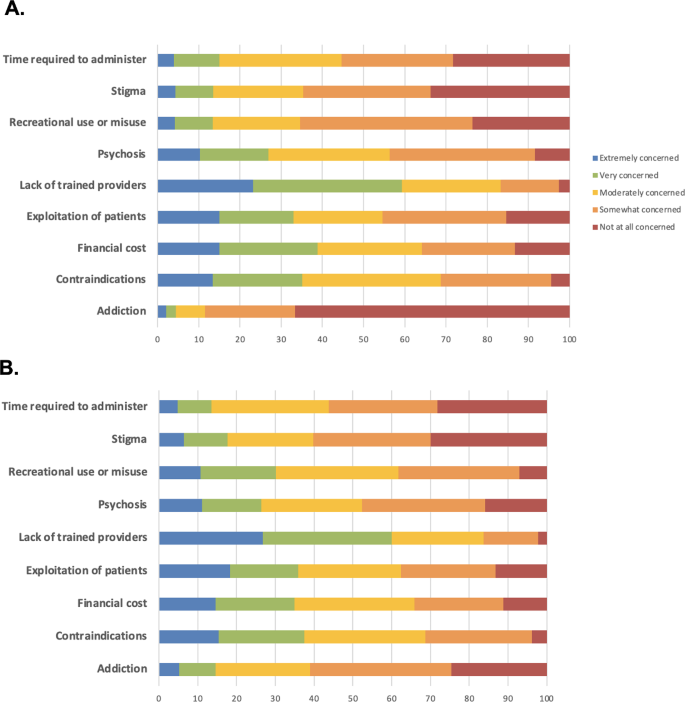

Concerns about Clinical Use of Psilocybin and MDMA. The most highly endorsed concerns regarding clinical administration of psilocybin were lack of trained providers (59% responded “extremely concerned” or “very concerned”), followed by financial costs / insurance coverage of psilocybin treatment (39%), potential harms to patients with contraindications (35%), potential exploitation of patients (33%), and potential for inducing psychosis (27%). The amount of time needed for psilocybin treatment (15%), stigma surrounding psilocybin (14%), recreational use of psilocybin (13%), and addictive potential of psilocybin (4%) were rated as less concerning (Fig. 2A).

The most highly endorsed concerns regarding clinical administration of MDMA were lack of trained providers (60%), followed by potential harms to patients with contraindications (38%), potential exploitation of patients (36%), financial costs / insurance coverage of MDMA treatment (35%), and recreational use of MDMA (30%). Potential for inducing psychosis (26%), stigma surrounding MDMA (18%), addictive potential of MDMA (15%), and amount of time needed for MDMA treatment (14%) were rated as less concerning (Fig. 2B).

Concern ratings for psilocybin (A) and MDMA (B). These figures show the proportion of respondents stating their level of concern (1 = not at all concerned and 5 = extremely concerned) for each of the following potential issues related to psilocybin and MDMA-assisted therapy.

MHPs reported the highest concern scores on average, followed by physicians and APPs, then RNs (Table 4). MHPs had greater concerns about administration to patients with contraindications, financial costs, and lack of trained providers. Physicians had greater concerns about recreational use and misuse.

Appropriate settings for psilocybin and MDMA therapies

Respondents regarded specialized clinics (93.9% for psilocybin, 90.1% for MDMA) to be the most appropriate clinical setting for the administration of psilocybin and MDMA, followed by private practice (78.6%, 68.9%), patient’s home with supervision (75.3%, 65.3%), outpatient clinics (63.5%, 58.5%), and detox/drug rehabilitation facilities (61.2%, 51.9%). Responses were similar between psilocybin and MDMA (Table 4). Slightly more respondents favored detox facilities and patient’s home (supervised and unsupervised) for psilocybin compared to MDMA.

Predictive models

Multivariable linear regression models were used to determine how professional role, demographic characteristics, knowledge, and personal experience predict healthcare professionals’ openness to clinical use of psilocybin and MDMA. Demographic variables predicted only a small proportion of total variance (R2 = 0.172; Supplemental Table S2). For psilocybin, openness to clinical use was significantly associated with prior personal experience using psychedelics and self-rated knowledge of psilocybin. Openness to clinical use of psilocybin significantly decreased as respondent age increased, with respondents who were 18–29 years old being most open to using psilocybin clinically, followed by those in the 30–49, 50–69, and 70 + year old age ranges. Average ratings of concern about psilocybin were not associated with openness to clinical use after adjusting for other covariates. APPs, RNs, and MHPs were more open to clinical use of psilocybin compared to physicians. Sex, race, and level of education were not significant predictors of openness to using psilocybin clinically.

Model findings for MDMA were similar to those of psilocybin. Demographic variables predicted only a small proportion of total variance (R2 = 0.204; Supplemental Table S3). For MDMA, openness to clinical use was significantly associated with prior personal experience using psychedelics and self-rated knowledge of MDMA. Openness to clinical use of psilocybin significantly decreased as respondent age increased, with respondents who were 18–29 years old being most open to using MDMA clinically, followed by those in the 30–49, and 50–69 year old age ranges. Average ratings of concern about MDMA were not associated with openness to clinical use after adjusting for other covariates. APPs, RNs, and MHPs were more open to clinical use of MDMA compared to physicians. American Indian race was associated with lower openness to clinical MDMA use. Otherwise, sex, race, and education level were not significant predictors of openness to clinical use of MDMA.

link

More Stories

New Resource Empowers Trauma Survivors and Health Professionals

Digital resource aims to enhance trauma-informed health care for people with complex PTSD

New resource supports trauma survivors, health professionals