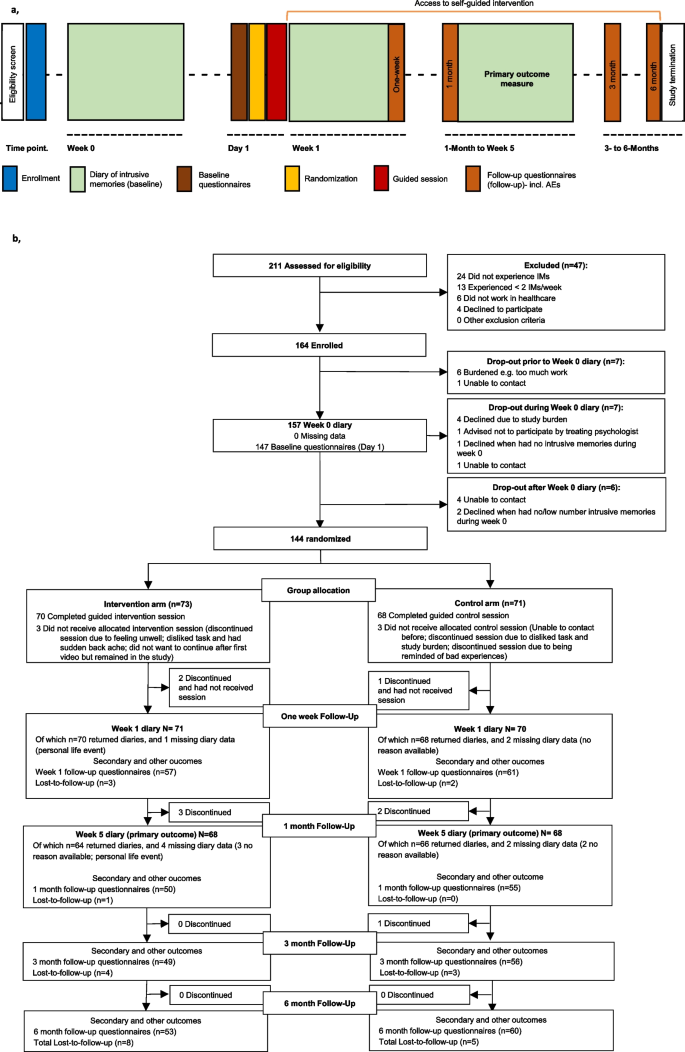

Two hundred and eleven participants were assessed for eligibility; of these, 164 were enrolled from 30 September 2020 to 27 April 2022 (final data were obtained on 31 October 2022). A total of 144 participants were randomised to the intervention (n = 73) and control (n = 71) arms (Fig. 1). The full analysis set consisted of all randomised participants as the ITT population (n = 144). During the guided session, 70 participants completed all components in the intervention arm, and 68 completed all components in the control arm. In total, 130 participants completed the whole study [control arm, n = 66 (93.0%); intervention arm, n = 64 (87.7%)], with 8 discontinuing before the primary endpoint. The primary outcome of the number of intrusive memories of traumatic event(s) was recorded in a daily diary for 7 days, at week 5. Of these, 118 participants completed data for all seven diary days and 12 completed partial diary data. The PP sample comprised 127 participants. Overall, 13 participants were lost to follow-up (control arm, n = 5; intervention arm, n = 8) and 9 discontinued (control arm, n = 4; intervention arm, n = 5). Thus overall (n = 144) there was an attrition rate of 6.3%.

Procedure timeline and participant flow diagram. a, Procedure timeline. After enrolment, participants completed a baseline diary recording number of intrusive memories (week 0) then completed baseline questionnaires. They were randomised to condition prior to the researcher-guided session (control or intervention) on day 1. During the following 7 days, participants completed a second diary (week 1), and completed week 1 follow-up questionnaires on day 8. During the study, participants could use the intervention self-guided (orange horizontal line). After completing the 1-month follow-up questionnaires, participants again completed the 7-day diary (week 5, primary outcome). Follow-up questionnaires were administered at 3 and 6 months. Total study duration was 176 days. AEs, adverse events. b, Participant flow (CONSORT diagram) indicating participant numbers throughout the course of the trial. Missing data refers to instances when a participant had no reported entries for that timepoint. IMs, intrusive memories. Lost-to-follow-up refers to participants who did not complete follow-up questionnaires up to 6 months

Baseline characteristics, traumatic events, post-traumatic stress and expectancy

Baseline characteristics were comparable between arms (Table 1). The mean (s.d.) age of the total sample was 41.41 ± 10.89 years. The majority of participants identified as female (81.9%), were full-time employees (70.8%) and worked as a nurse (58.3%).

The mean number of work-related traumatic events during the pandemic at baseline was 17.02 (± 21.38), and the majority (72.2%) were experienced in the previous 1–3 months. In addition, participants reported an average of 9.18 ± 28.53 non-work-related traumatic events during the pandemic. The number of prior psychological traumas was indexed using LEC-5 [58] (Table 1).

The mean (s.d.) post-traumatic stress symptoms score at baseline was 12.10 ± 6.63 (scale ranging from 0–32, with cut-off for clinical importance typically set at 19; (PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, 8 item version, PCL-5) [60]. The post-traumatic distress score was 15.29 ± 6.07 and 13.72 ± 6.85 for intrusion and avoidance subscales, respectively (sum score of each scale ranging from 0–32 using the IES-R) [61]. Eighty participants (55.6%) reported a current or past mental health condition (Additional file 1, Table S1).

At baseline (week 0), the median number of intrusive memories recorded in a daily diary for one week was similar between arms (combined median = 15.00; IQR = 7.5–28.5, n = 118) (Additional file 1, Table S7a (complete diary data) and S7b (incomplete diary), day-by-day Additional file 1, Fig. S1A).

At baseline (day 1, after randomisation and prior to intervention), participants’ expectations that their assigned task would help reduce intrusive memories were low (credibility scale maximum = 54) and differed between arms, with lower credibility/expectancy ratings in the intervention group (mean ± s.d.: control: 24.67 ± 8.91, n = 69; intervention: 20.21 ± 11.57, n = 73; OR = 0.45, (95% CI = 0.25–0.80), P = 0.0072], (Table 1). See Table 1 and Additional file 1, Table S1 and Tables S7 to S10 for further baseline data.

Primary outcome

Number of intrusive memories of traumatic events (week 5)

The primary outcome was the Number of intrusive memories recorded in a daily diary during week 5 after the intervention/control task. The pre-specified primary analysis was ITT (i.e., n = 71 control arm; n = 73 intervention arm). Sixty-six participants in the control arm and 64 in the intervention arm returned the daily diary at week 5 (Fig. 1). Six participants did not adhere to the task (control arm: n = 3; intervention arm: n = 3) (Table 2)

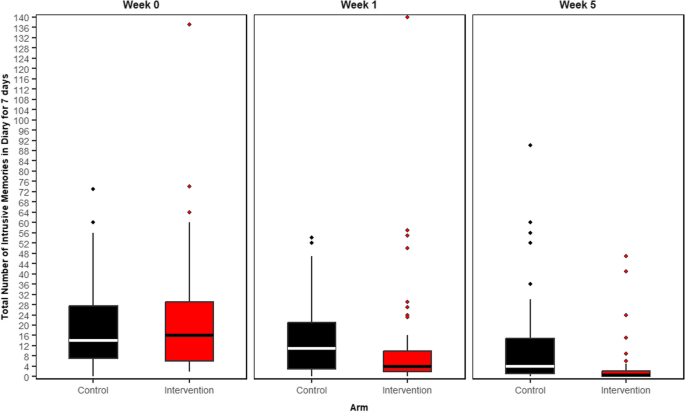

Participants in the intervention arm reported significantly fewer intrusive memories at week 5 than did those in the control arm using the ITT sample (summary of the outcome per arm: control arm Mdn = 5.0 (IQR = 1–17), n = 58; intervention arm Mdn = 1.0 (IQR = 0–3), n = 60; IRR based on imputed data = 0.30 (95% CI = 0.17–0.53); p < 0.0001 (Table 2, Fig. 2 and for day-by-day Additional file 1, Fig. S1C). The baseline number of intrusive memories (at days -7 to -1) has been included as a covariate.

Number of intrusive memories of work-related traumatic events per condition at each of three time points: week 0 (pre-intervention baseline), week 1 (immediately post-intervention) and over week 5 (primary outcome)

Boxplots show number of intrusive memories of traumatic events, whereby the midline is the median value. Upper and lower box limits are the third and first quartile (75th and 25th percentile), with the whiskers covering 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). All outliers are included in this figure and shown as dots (each dot represents one participant that departed by more than 1.5 times the IQR above the third quartile and below the first quartile). Number of intrusive memories of traumatic events are recorded by participants in a brief daily online intrusive memory diary for 7 days (daily diary)

The figure is based on diary data available in the ITT sample, including incomplete diary data, for week 0: n = 144, week 1: n = 136, and week 5: n = 130

The imagery-competing task intervention consisted of a cognitive task involving a brief memory cue plus Tetris® computer gameplay with mental rotation instructions, with a first guided session with the researcher

The active control (attention-based placebo comparator) consisted of a cognitive task that also involved a digital activity and, for the same amount of time, listening to a podcast on philosophy, with a first guided session with the researcher

Week 0: Baseline measure. Number of intrusive memories in the daily diary during the baseline week for both arms (black = control arm, n = 71: attention-based placebo control; red = intervention arm, n = 73: remotely-delivered, imagery-competing task intervention) showing that the two arms did not differ at baseline (i.e., before the intervention was provided to either arm)

Week 1: Secondary outcome measure. Number of intrusive memories in the daily diary during week 1 for each arm (black = control arm, n = 67: attention-based placebo control; red = intervention arm, n = 69: remotely-delivered, imagery-competing task intervention). The intervention arm had fewer intrusive memories at week 1 compared to the control arm

Week 5: Primary outcome measure. Number of intrusive memories of traumatic events recorded by participants in a brief daily online intrusive memory diary for 7 days during week 5 for both arms (black = control arm, n = 66: attention-based placebo control; red = intervention arm, n = 64: remotely-delivered, imagery-competing task intervention). The intervention arm had fewer intrusive memories at week 5 compared to the control arm

Sensitivity analyses evaluating the robustness of treatment effect showed this difference remained significant using a pre-specified PP population (Table 2). Additional sensitivity analyses showed that using a non-parametric Wilcoxon’s test (Additional file 1, Table S11) and with imputed data using MAR (Additional file 1, Table S12) and using missing not at random (MNAR) assumption (Additional file 1, Table S13), and exclusion of outliers (Additional file 1, Table S14) as well as excluding diary missing data (completers only), the pattern of results remained (Additional file 1, Table S15).

Gender and age-distributed descriptive data regarding the primary outcome (Additional file 1, Tables S16 and S17) appeared comparable for women and men and across age levels.

Secondary outcomes

Number of intrusive memories of traumatic events (week 1)

Participants in the intervention arm reported significantly fewer intrusive memories of traumatic events in the daily diary during the week after the guided session (week 1) than did those in the control arm [control arm Mdn = 11 (IQR = 3–21), n = 65; intervention arm Mdn = 4.5 (IQR = 2–10.5), n = 64; IRR based on imputed data = 0.53 (95% CI = 0.41–0.70); p < 0.0001] (Fig. 2, Additional file 1, Table S12, day-by-day Fig. S1B).

At the end of each week 0 and 1 and start of week 5, participants completed an intrusion diary. They also provided a retrospective rating of their intrusive memory frequency during the previous week (intrusion questionnaire; IQ [59]) (Additional file 1, Table S2). Correlations were calculated to explore convergence between diary data at weeks 0, 1 and 5, and corresponding IQ ratings. This showed that the total number of intrusive memories reported in the diary and IQ ratings were significantly correlated at all timepoints (baseline: r = 0.745, p < 0.0001, week 1: r = 0.793, p < 0.0001, week 5: r = 0.651, p < 0.0001).

Clinical symptoms

Post-traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic distress

Relative to the control arm, participants in the intervention arm reported significantly less post-traumatic stress symptoms (PCL-5 short version 8-item scale) at each timepoint from week 1 through to the 6 month follow-up [week 1 mean ± s.d: control: 10.57 ± 6.91, n = 61; intervention: 6.91 ± 6.15, n = 54; OR = 0.37 (95% CI = 0.19–0.71), p < 0.0031, 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 10.38 ± 7.30, n = 55; intervention: 4.90 ± 5.29, n = 51; OR = 0.21 (95% CI = 0.10–0.42), p < 0.0001, 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 8.98 ± 6.92, n = 55; intervention: 3.81 ± 5.17, n = 47; OR = 0.19 (95% CI = 0.09–0.40), p < 0.0001, 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 8.36 ± 6.47, n = 58; intervention: 3.46 ± 4.83, n = 52; OR = 0.19 (95% CI = 0.09–0.39), p < 0.0001] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Participants in the intervention arm reported lower post-traumatic distress related to intrusions than those in the control arm at each timepoint from week 1 post-intervention to the 6 month follow-up (IES-R intrusions subscale sum score) [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 13.44 ± 6.59, n = 61; intervention: 8.36 ± 6.01, n = 56; OR = 0.24 (95% CI = 0.12–0.49), p < 0.0001, 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 11.63 ± 7.44, n = 56; intervention: 5.25 ± 5.51, n = 51; OR = 0.16 (95% CI = 0.08–0.34), p < 0.0001, 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 9.52 ± 6.55, n = 56; intervention: 4.18 ± 5.16, n = 49; OR = 0.17 (95% CI = 0.08–0.34), p < 0.0001, 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 8.87 ± 6.74, n = 60; intervention: 4.36 ± 5.00, n = 53; OR = 0.25 (95% CI = 0.12–0.49), p < 0.0001]. Avoidance scores in the intervention arm were lower at each timepoint from 1 to 6 months (IES-R avoidance subscale) [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 11.48 ± 6.83, n = 61; intervention: 10.43 ± 7.15, n = 56; OR = 0.73 (95% CI = 0.39–1.38), p = 0.34, 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 10.79 ± 7.42, n = 56; intervention: 6.06 ± 7.06, n = 51; OR = 0.25 (95% CI = 0.12–0.51), p = 0.0002, 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 9.14 ± 6.75, n = 56; intervention: 4.96 ± 6.48, n = 49; OR = 0.26 (95% CI = 0.12–0.52), p = 0.0002, 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 7.75 ± 6.80, n = 60; intervention: 4.77 ± 5.74, n = 53; OR = 0.41 (95% CI = 0.21–0.79), p = 0.0082] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Self-reported characteristics of intrusive memories can be found in Additional file 1, Table S2 and Table S1 for baseline.

Other outcome measures including functioning

Work engagement and burnout (SWEBO at 6 months) differed between arms, whereby participants in the intervention arm reported a lower total burnout score, with lower scores on two subscales [SWEBO: total mean ± s.d.: control: 1.80 ± 1.56, n = 58; intervention: 1.56 ± 0.58, n = 50; OR = 0.46 (95% CI = 0.23–0.90), p = 0.0240; disengagement subscale mean ± s.d.: control: 1.66 ± 0.66, n = 58; intervention: 1.42 ± 0.60, n = 50; OR = 0.45 (95% CI = 0.22–0.90), p = 0.0245; inattentiveness subscale mean ± s.d.: control: 1.78 ± 0.65, n = 58; intervention: 1.49 ± 0.40, n = 50; OR = 0.40 (0.20–0.80), p = 0.0102] (Additional file 1, Table S2). There was no difference in the amount of sick leave between arms (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Participants in the intervention arm reported lower stress, pressure and tenseness at work (SEQ – stress subscale) at 1 month [mean ± s.d.: control: 6.42 ± 3.53, n = 55; intervention: 4.25 ± 2.69, n = 48; OR = 0.33 (95% CI = 0.16–0.66), p = 0.0018] with no difference at other timepoints (Additional file 1, Table S2). Moral stress at work was significantly lower (i.e., higher ratings) in the intervention relative to control arm at 1 month only [mean ± s.d.: control: 13.44 ± 3.81, n = 55; intervention: 15.21 ± 3.11, n = 48; OR = 2.28 (95% CI = 1.15–4.57), p = 0.0189] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

General functioning (WHODAS at 6 months) was better in the intervention compared to the control arm in the domains of cognition [mean ± s.d.: control: 3.59 ± 1.55, n = 58; intervention: 3.16 ± 1.71, n = 50; OR = 0.48 (95% CI = 0.23–0.96), p = 0.0400] and personal care [mean ± s.d.: control: 2.55 ± 1.16, n = 58; intervention: 2.20 ± 0.81, n = 50; OR = 0.30 (95% CI = 0.08–0.91), p = 0.0469]. There was no significant difference between arms for the domains of mobility, relations, daily activities, participation in society or disability score. Frequency of difficulties within a week were lower in the intervention arm compared to the control arm [mean ± s.d.: control: 1.97 ± 2.41, n = 58; intervention: 0.88 ± 1.85, n = 50; OR = 0.31 (95% CI = 0.14–0.66), p = 0.0027], with no difference regarding the impact of difficulties (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Self-rated health (SRHR) was better (i.e., higher ratings) in the intervention arm at all timepoints [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 3.59 ± 1.05, n = 60; intervention: 4.44 ± 1.18, n = 54; OR = 2.61 (95% CI = 1.32–5.26), p = 0.0066; 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 3.89 ± 1.52, n = 55; intervention: 4.68 ± 1.19, n = 50; OR = 2.84 (95% CI = 1.41–5.87), p = 0.0041; 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 4.11 ± 1.07, n = 53; intervention: 4.67 ± 1.17, n = 46; OR = 3.13 (95% CI = 1.48–6.80), p = 0.0033; 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 4.10. ± 1.17, n = 58; intervention: 4.67 ± 1.22, n = 52; OR = 2.82 (95% CI = 1.40–5.82), p = 0.0041] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Self-rated sleep ratings (SCI–02) were higher (indicating better sleep) in the intervention arm relative to the control arm from week 1 to 3 months [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 4.92 ± 2.30, n = 60; intervention: 5.89 ± 2.45, n = 54; OR = 2.61 (95% CI = 1.34–5.17), p = 0.0053; 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 4.65 ± 2.82, n = 55; intervention: 6.02 ± 2.10, n = 50; OR = 2.16 (95% CI = 1.09–4.33), p = 0.0293; 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 4.77 ± 2.33, n = 53; intervention: 6.28 ± 2.05, n = 46; OR = 3.92 (95% CI = 1.88–3.38), p = 0.0003] Though at 6 months, there was no significant difference [6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 5.40 ± 2.41, n = 58; intervention: 6.23 ± 1.83, n = 52; OR = 1.85 (95% CI = 0.95–3.64), p = 0.0742] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

On the intrusive memory ratings, participants in the intervention condition reported less concentration disruption due to intrusive memories (assessed by a single rating on a scale from 0–10 [29] in the intrusion diary at weeks 1 and 5) compared to the control arm at both timepoints [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 2.77 ± 2.06, n = 57; intervention: 1.92 ± 2.23, n = 51; OR = 0.40 (95% CI = 0.20–0.79), p = 0.0092; week 5 mean ± s.d.: control: 2.67 ± 2.31, n = 46; intervention: 1.78 ± 2.26, n = 27; OR = 0.39 (95% CI = 0.16–0.91), p = 0.0321] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

At 6 months, participants in the intervention arm reported less concentration and memory difficulties (i.e., higher ratings on an 11-item scale [70, 71]) than the control arm [mean ± s.d.: control: 38.17 ± 10.84, n = 52; intervention: 44.55 ± 7.93, n = 42; OR = 3.36 (95% CI = 1.62–7.14), p = 0.0013] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Participants in the intervention arm rated their intrusive memories as having less impact on occupational functioning [25] at each timepoint from 1 month to the 6 month follow-up relative to the control arm [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 2.69 ± 2.74, n = 61; intervention: 1.72 ± 1.96, n = 54; OR = 0.56 (95% CI = 0.29–1.07), p = 0.0816;1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 2.96 ± 2.66, n = 55; intervention: 1.20 ± 1.97, n = 42; OR = 0.22 (95% CI = 0.10–0.45), p < 0.0001; 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 2.20 ± 2.36, n = 55; intervention: 0.87 ± 1.60, n = 47; OR = 0.30 (95% CI = 0.14–0.63), p = 0.0016; 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 2.10 ± 2.11, n = 58; intervention: 1.06 ± 1.87, n = 51; OR = 0.28 (95% CI = 0.13–0.56), p = 0.0005] (Additional file 1, Table S2). Similarly at each timepoint, participants in the intervention arm reported that intrusive memories had less impact on daily functioning in other areas than the control arm [week 1 mean ± s.d.: control: 4.03 ± 2.71, n = 61; intervention: 2.85 ± 2.10, n = 54; OR = 0.47 (95% CI = 0.24–0.90), p = 0.0243; 1 month mean ± s.d.: control: 3.91 ± 2.41, n = 55; intervention: 2.42 ± 2.22, n = 50; OR = 0.24 (95% CI = 0.11–0.49), p = 0.0001; 3 months mean ± s.d.: control: 3.51 ± 2.46, n = 55; intervention: 1.89 ± 1.66, n = 47; OR = 0.23 (95% CI = 0.11–0.49), p = 0.0002; 6 months mean ± s.d.: control: 3.17 ± 2.19, n = 58; intervention: 2.02 ± 1.87, n = 51; OR = 0.26 (95% CI = 0.12–0.53), p = 0.0003] (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Other measures (including letting go of work-related thoughts, social support, coping, appraisal of intrusions, future self-identity, time perspective questionnaire, work situation) can be found in Additional file 1, Secondary and Other Pre-specified Outcomes Descriptions 2–4 and Additional file 1, Table S2.

Assessments related to procedures

Feedback on acceptability and feasibility, how upsetting it was to do the task, and subsequent use of task on their own is in Additional file 1, Table S18. Number of hotspots (i.e. different intrusive memories in intervention arm only), days/nights worked during diary completion weeks, booster sessions, and additional traumatic events during the study are in Additional file 1, Table S19.

Safety

Number of adverse events (AEs) are reported in Additional file 1, Table S3 and types of AEs in Additional file 1, Table S4. In total, 183 AEs were reported during the 6 months. Overall, 74 (51.4%) participants reported at least one AE [36 (49.3%) in intervention arm and 38 (53.5%) in control arm, p = 0.6136]. There were no serious adverse events (SAEs). Three AEs were assessed as severe (cancer treatment; burnout; PTSD), of which none were study-related, 49 were assessed as moderate and 131 as mild (Additional file 1, Table S3). Control participants reported more AEs (n = 119) than those in the intervention arm (n = 64), p = 0.0052.

link

More Stories

Edward Hines Junior Hospital | VA Hines Health Care

healthcare disparities Archives – Milwaukee Community Journal

Crow mother thanks and celebrates healthcare workers who saved her life