Six hundred and sixty-six participants responded to the study invitation, of whom 383 completed the questionnaires. Fifty-one participants who lived in different households from the HCW and twelve participants who did not complete the STSS were excluded. In total, 320 participants completed all relevant questions and were included in the statistical analyses.

Out of 320 participants, 142 household members were female, and 171 household members were male. Seven household members preferred not to share their sex. Two hundred and seventy-four of the participants described their ethnicity as white. Out of 320 participants, 258 were spouses or partners of HCWs. Two hundred and thirty-found of the participants reported that their HCW loved one worked in a clinical role with direct contact with patients. See Table 1 below for the participants’ characteristics.

Quantitative analysis

A third of the participants (n = 108) reported severe secondary traumatic stress scores (M = 61, SD = 8.2). Around 10% of the participants reported high (n = 33) secondary traumatic stress scores, 16% reported moderate (n = 51), 23.8% reported mild (n = 76), and 23.1% reported low or no STS (n = 74) scores.

To test our first hypothesis, we conducted a two-tailed t-test, and we found that female household members (n = 142) reported significantly higher secondary traumatic stress (M = 44.1, SD = 17.8) compared with male (n = 171) household members (M = 40.3, SD = 15.1), t(311) = 2.03, p <.005. We also found that spouses and partners of HCWs reported significantly higher STS (M = 44, SD = 16.6), compared with other household members who reported lower STS (M = 35, SD = 13.5), t(318) = 3.85, p <.001. Household members of HCWs with clinical roles showed significantly higher STS (M = 44.1, SD = 16.7) compared to household members of HCWs with non-clinical roles (M = 36.1, SD = 14.1), t(318) = 3.7, p <.001. Household members’ secondary traumatic stress scores did not significantly differ based on their ethnicities or their ages.

Bivariate correlations were run independently amongst the six variables (sex, age, ethnicity, HCW’s job role, relationship with the HCW, and STS) (See Table 2). There was a positive correlation between STS scores and being female, being a spouse or partner of an HCW, and living with a HCW with a clinical role. There was no significant correlation between STS and ethnicity.

Multivariable linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of STS, specifically sex, age, job role of the HCW, and the relationship with the HCW. The overall model was statistically significant (F(5, 314) = 9.53, p <.001), and accounted for approximately 36% of the variance in STS scores. As shown in the Table 3, sex, HCW’s job role, and the relationship with the HCW were significant predictors of STS. Specifically, STS was positively associated with having a HCW household member with a clinical role (r(314) = 0.215, p <.001) and being a spouse/partner of a HCW (r(314) = 0.246, p <.001). Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs). All VIF values ranged between 1.02 and 1.8, well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern in this model. In summary, based on the multivariable linear regression models’ findings, being a spouse/partner of a HCW and living with a HCW with a clinical role were predictors for high STS, after controlling for sex and age (See Table 3).

Model summary

F(5, 314) = 9.53, p <.001, R² = 0.36, Adjusted R² = 0.12.

Qualitative content analysis

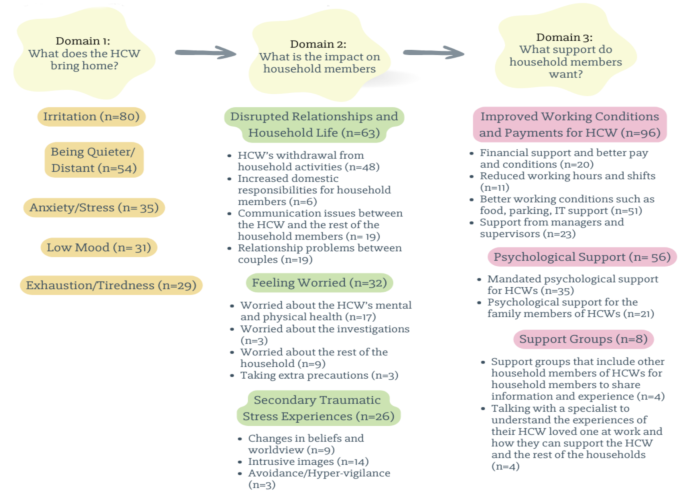

Out of 332 participants, 267 household members provided information in response to the open-ended questions. We deductively organised our analysis into three domains, within which we identified a number of inductive categories and subcategories (See Fig. 1).

Domains, categories, subcategories, and number of participants

What HCWs bring home

Out of 267 participants who responded to this open-ended question, 102 household members reported that when the HCW had had a difficult day at work, that they experienced changes in the HCW’s behaviour. For example, 80 household members observed that the HCW was more irritated, angry, and easily annoyed, after a difficult day at work compared to other days. Additionally, 35 household members reported that the HCW was more anxious, 31 of them reported that the HCW had lower mood and 29 household members observed that the HCW was more exhausted. Fifty-four household members of HCWs pointed out that after a difficult day at work, their HCW loved one tended to be quieter and distant from the rest of the household members. Some noted that on those difficult days, HCWs tend to be less empathetic and compassionate to the rest of the household. For example,

“[She] is struggling to sleep/worrying about specific patients and/or her clinical decision/action/inaction. If she feels like her work is incomplete or her clients are not ok until she next sees them she is worried and so grumpy and cranky with me.” (A partner of a nurse).

Impacts of healthcare workers’ distress on household members

Out of 267 household members who answered this question, 130 household members reported that the HCW’s work had affected themselves and the rest of the household in the ways detailed below.

Disrupted relationships and household life

Sixty-one household members said that their household life and relationships were disrupted due to the HCW’s job. For example, 48 household members pointed out that as a consequence of their HCW household member coming home from work and being upset, frustrated, or low in mood, that he/she did not want to participate in household activities. A male partner of a nurse shared his experiences below:

[She is] in low mood, short tempered, doesn’t want to be around others, only watches TV/reads a book alone. She does not want to participate in any family activities after work.

Similarly, 24 household members reported that the demanding nature of the HCW household members’ work impacted on the rest of the household, making it difficult to plan household activities. For instance, a female partner of a healthcare assistant reported that:

Work schedules change every 3 months to suit needs of the hospital which makes planning my own work schedule and our joint social events much more complicated. The lack of staff at my partner’s workplace also means there are only two points in the year they can take off a whole week of work at one time which limits how we plan family vacations and time off.

Similarly, the male husband of an administrator shared his experiences with these words;

I do feel like my husband had a choice to go into the work he has, but I don’t have a choice around how it impacts us as a family or as a partnership. He chose that work, I didn’t, and so when he is then less available at home emotionally or socially that leaves a greater burden on me and also means we are losing out on the best of him because work gets that a lot of the time.

Due to workloads and long shifts, HCWs tended to come home mentally and physically tired. Six household members specifically reported that as a result of this they had to take on more domestic responsibilities. For example, the female wife of a psychologist shared her experiences below:

“[Psychologist HCW] required to work overtime and thus impacting on childcare, household tasks. Their work takes priority, so family life and school pick up arrangements are changed in response to that”.

Six household members reported that HCWs struggled to separate home and work life. Due to feeling like their HCW household member was distant of cut off, four participants described how this made them feel like they were not a priority for the HCW. Nineteen household members reported that the HCWs’ feelings and behaviours created communication problems with other household members. For example,

“I feel like my partner is overworking and prioritising work over me” (Female partner of other allied health professional).

“They did not share their experiences, they felt they needed to be strong and never got help from us or therapy. It ruined our family. We never speak at home, we never hug, our lives as a family are secondary to their work” (Son of a consultant doctor).

Specifically, 19 spouses and partners reported relationship problems due to a lack of intimacy, empathy, and compassion. For example, the wife of a doctor reported that.

“My husband is frequently angry and feels miserable. Our daughter has had depression as a result. My husband all but stopped having sex, only watches TV at home and before going to work” (Female wife of a doctor).

Feeling worried

Thirty-two household members reported that they had felt worried due to the nature of the HCW’s job. For instance, 17 household members pointed out that they were worried about their HCW household member’s mental health and physical health.

I have been worried for her physical and mental wellbeing. Some examples: Twice a week for a year she worked alone late at night running a clinic with patients who were often angry, with no panic button and no way to escape the room, and no action from her superiors when the issue was raised. She has frequently been verbally, sexually, and physically attacked by patients on the ward, sometimes with weapons, and it being laughed off by other staff. During covid she was sent onto ICU without a mask which fitted, which resulted in her getting covid. Repeatedly being discriminated against by her superiors due to her race and/or gender. I am convinced that one day this job will kill her, if not directly then by driving her to suicide. (Male husband of a pharmacist)

Three of the spouses and partners of HCWs reported that HCWs were working too long and that this could make them open to making mistakes. For this reason, some of the household members pointed out that they were worried about potential litigation. For example, a female wife of an allied health professional shared her feelings with us with these words:

Patient complaint police involved poorly handled by trust husband was distraught and felt no one believed him, and effect on him and kids. [I felt] fear of jail and there was a lack of belief and support from trust.

Nine household members stated that they were also worried about the mental and physical health of the rest of the household members. For example, a female partner of an allied health professional said that due to the infection risk that the HCW could bring home, she was worried and taking more precautions in terms of hand hygiene and general increase in anti-bacterial cleaning. Additionally, some household members reported that they were worried about their own safety due to their HCW household member’s job. For example,

“I concern about mentally unstable colleague who knew where we lived. Made me worry for our safety.” (Female partner of a psychologist).

Secondary traumatic stress experiences

Out of 266 household members who responded to this question, 102 household members reported that they had been troubled by traumatic experiences related to their HCW household members’ work that the HCWs had shared with them. For example, 26 household members described experiences consistent with secondary traumatic stress. Several stated that there was a real physical threat for HCWs, and this impacted the whole household. Nine household members reported that after hearing about the traumatic experiences of HCWs, they started to question humanity and the safety of the world, and reported changes in their beliefs and world view. For example,

“They have had to work with some very difficult cases which make me worried about humanity.” (A male husband of a psychologist).

“[I feel] distress when I remember the stories of her patients and their lives and/or recount the traumatic stories of her clients (NB her client group is the homeless population). Worry about the state of the NHS and its ability to provide for me and my family. Overwhelmed by state of the world that’s resulting in her client’s situations.” (Female partner of a nurse).

HCWs’ traumatic experiences triggered household members’ previous traumatic experiences as well. For example, a nurse’s male partner who also worked in PICU stated that his partner’s experiences were triggering for him.

She would often offload her stress when she comes home, which is fine with me, although I had worked on a PICU before, so could touch lightly on my own trauma from the ward.

The female friend of a chaplain also reported that,

Talking about people’s death through cancer, remind me of my grandfather’s death when I was a child aged 4.

Fourteen household members reported that they experienced intrusive, repetitive images in their minds and associated distress related to the traumatic experiences their HCW household member had told them about.

“Some of the images and stories [that the doctor partner shared] are quite shocking and play over in my mind.” (Female partner of a doctor).

“Significantly concerned about partner’s safety and mental wellbeing. Incidents that I’ve been told about coming back to me at random moments and triggering emotional response – fear, sadness, hopelessness, anxiety.” (Female wife of an occupational therapist).

Three household members reported avoidance and hypervigilance related to their HCW loved one’s traumatic experiences. For instance, a male husband of a nurse shared his experiences after the HCW’s traumatic experiences with these words;

Someone made threats to kill him, this was a problem for many months. He works also close to where we live. So, we all became hypervigilant, would not go out for meal or socialising, because we think that that person can kill us too.

Support that household members need

This question related to what kinds of support participants thought could be helpful for household members and was answered by 130 household members, as detailed below.

Improved working conditions and pay

Ninety-six household members reported that the priority in supporting the mental health and wellbeing of the household members (including the risk of developing mental health issues) was primarily for HCWs to be better looked after, and that their working conditions and pay needed to be improved. Some of the household members reported that when HCWs’ basic needs are met, the risk of developing mental health and wellbeing issues for the household members may also be reduced. Twenty household members pointed out that providing financial support and better remuneration was required to support healthcare workers and their households. Fifty-one household members reported that HCWs’ working environments needed to be improved. Some of the household members reported that the unsafe work environment of the HCWs impacts their mental health and wellbeing in a negative way as well. For example, a male husband of a nurse shared his thoughts with these words;

Generally speaking I worry about her safety at work and being attacked/abused by patients/clients. The facilities are not there to provide a safe environment and the nature of her job means her wellbeing and physical safety are suffering detriment. There is also not adequate facilities to work remotely without causing back pain and she doesn’t feel able to ask. I would like better equipment, IT, money and proper cover so she’s not feeling guilty when she takes annual leave and her clinics aren’t covered by anyone. I also feel very angry with the lack of respect and pay that nurses get compared to doctors, it’s hierarchical where nurses are bearing huge amounts of emotional/mental burden and doing more and more that doctors do but they are STILL seeming as ‘less’ than a doctor.

Additionally, household members also pointed out that working conditions and lack of resources need to be addressed. A male husband of a psychotherapist said that,

A part time job should be part time and not eat into all hours! NHS staff are HUGELY underpaid, undervalued and way way way OVERWORKED.

Twenty-three household members stated that their HCW loved one was not getting enough support from their supervisors and managers and this needed to be improved. For instance,

“The best support I can have [as a partner of a HCW] is to make sure they are well supported and managed.” (Male partner of other allied health professional).

Psychological support

Fifty-six household members commented that their HCW loved ones and the household members needed psychological support. Thirty-five household members suggested that mandatory psychological support would be helpful for HCWs, and indirectly household members.

“More support for my partner in work with coping with workplace incidents, inconveniences and general stress. An outlet in work for raising issues that have caused grief, how to overcome them and avoid a repeat. Not leaving the issue to linger or grow out of control.” (Male partner of a nurse).

Twenty-one participants also suggested that household members would benefit from psychological support as they are also impacted psychologically by supporting their HCW loved ones. A female partner of a physiotherapist wrote,

My partner is a physiotherapist and worked on the ‘frontline’ during COVID-19. He came home most days saying he had a good day. It was only months later that he disclosed he had PTSD and felt he needed counselling. I felt that I had failed him, and the stories he shared with me of patients dying were deeply distressing. Now, I need psychological support too.

Group-based support

Four household members suggested that they would benefit from group-based support including other household members of HCWs. They felt this would facilitate information sharing and social support for each other. For example, the wife of a psychologist stated that,

It could be nice to have a social group including other family members [of other HCWs] or a support group for those impacted.

Four household members pointed out that they sometimes felt like they did not understand what their HCW household members experienced and they did not best know how to support the HCW loved one, the rest of the household, and themselves. For this reason, these participants suggested that receiving professional support could be helpful.

“The NHS do not give enough recognition to the families behind the worker. For example, when the workers have a tough time at work, and they cannot divulge all the confidential information. It’s like trying to support them without having someone who could give me some advice on how to deal with things that might make things better for him or for the rest of the family.” (Male husband of an administrator).

link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Health-GettyImages-1326218528-713669ce38eb405a81854216f176d965.jpg)

More Stories

Are Paramedicine Students Experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress as a Result of a Clinical Rotation?

Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare professional: systematic review and a meta-analysis based on correlation coefficient

Violence against health workers must end