This summer, a male patient at Specialist Hospital Damaturu in Nigeria’s Yobe State physically assaulted a female healthcare worker following a dispute over the provision of medical attention.

Sadly, this is a relatively common experience for healthcare workers in Nigeria, especially women. Surveys conducted in hospitals in Kaduna state and Abia state found 64% and 88% of health workers, respectively, had experienced workplace violence.

During my own first year of clinical practice in Nigeria, when I was just 24 years old, I was attacked by a parent in the children’s ward where I worked.

Nigeria is not alone. Reports of violence against healthcare workers have been on the rise over the last five years in a wide range of countries, including Ireland, Britain, Australia, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Turkey, and the United States.

A 2019 study showed 11% of nurses in Italy had endured physical violence at work in the previous year, and 4% were threatened with a firearm. About half of all nurses reported experiencing verbal aggression.

Such reporting tells only part of the story. The belief violence is “part of the job”, together with the lack of protocols for handling attacks and the empathy of many in the healthcare field, discourages reporting.

When I was attacked in 2004 — narrowly avoiding a severe head injury, thanks only to the swift intervention of another patient’s relative — I eschewed legal prosecution out of sympathy for the perpetrator’s family, which was, after all, grappling with a child’s illness and subsequent death.

With this in mind, the World Health Organization estimates as many as 38% of healthcare workers suffer some form of physical violence, perpetrated mostly by patients and visitors, at some point in their careers.

This figure does not cover the verbal threats and intimidation many workers face as they carry out life-saving work, often under high-stress, low-resource conditions.

Several factors contribute to the violence. Healthcare workers are often younger women. They must work both day and night shifts in environments that are accessible to the general public, including people who have consumed drugs or alcohol, and people suffering from psychiatric illnesses.

Moreover, staff and resource shortages mean healthcare workers are often overworked, underpaid, and lack access to the tools they need to deliver quality or timely care.

Long wait times increase stress and frustration among patients (and their relatives), who often expect miracles, even when they present late for treatment. Add to that poor communication and weak workplace protections, and violence becomes a constant peril.

Risks to healthcare workers are particularly acute in disaster, conflict, and other humanitarian settings, where they may also become the targets of political or communal violence.

As a result of these experiences, healthcare workers often deal with anxiety, depression, job burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental health conditions. One study found some 76% of psychiatric nurses who suffered from workplace violence subsequently experienced depressive symptoms.

As health workers’ wellbeing declines, so does the care patients receive. Increased absenteeism and turnover compound the problem, especially as fewer people choose to enter the healthcare field. At a time when the world is facing a shortage of healthcare workers — projected to reach 10 million by 2030 — this poses a direct threat to public health.

Protecting healthcare workers will require a variety of interventions. For starters, violence prevention and response should be integrated into workers’ education and training. They should be taught communication strategies for de-escalating tense situations, and self-defence techniques to use if violence erupts. Team-based training can strengthen coordinated responses, enabling other workers to intervene when their colleagues are targeted.

Furthermore, the scope and enforcement of existing worker-protection laws must be enhanced. Institutions must implement zero-tolerance guidelines, with clear protocols for monitoring workplace safety, reporting and investigating incidents, and bringing legal action against offenders.

The swift arrest and prosecution of perpetrators — as seen after the recent attack at Specialist Hospital Damaturu — can act as a deterrent. Hiring trained security personnel would also help, as would the implementation of reliable communication systems that enable workers to sound the alarm when their safety is threatened.

Meanwhile, a concerted effort must be made to address health worker shortages, such as through task-shifting or -sharing — the partial or complete redistribution of certain responsibilities to less qualified personnel, so highly qualified workers can focus on tasks that require their expertise.

Already, this approach has improved service delivery in a number of areas — including HIV/Aids, tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes, mental health, eyecare, maternal and child health, sexual and reproductive health, and emergency care — in 23 Sub-Saharan African countries.

All people have a right to safety in their workplace. When we fail to uphold this right for healthcare workers, we hurt not only them, but also the health of the public they serve.

- Adaeze Oreh is commissioner for health in Rivers State, Nigeria, a Kofi Annan Global Health Leadership fellow, and an Aspen Global Innovators senior fellow.

- Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025. project-syndicate.org

link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/stuffy-nose-GettyImages-854418348-39f4f61c549946d4bd586786909ad47c.jpg)

More Stories

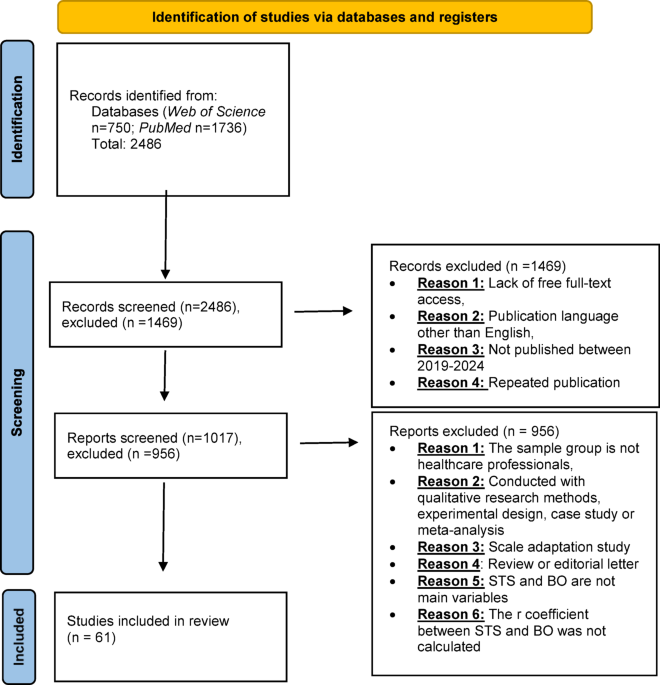

Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare professional: systematic review and a meta-analysis based on correlation coefficient

Edward Hines Junior Hospital | VA Hines Health Care

healthcare disparities Archives – Milwaukee Community Journal