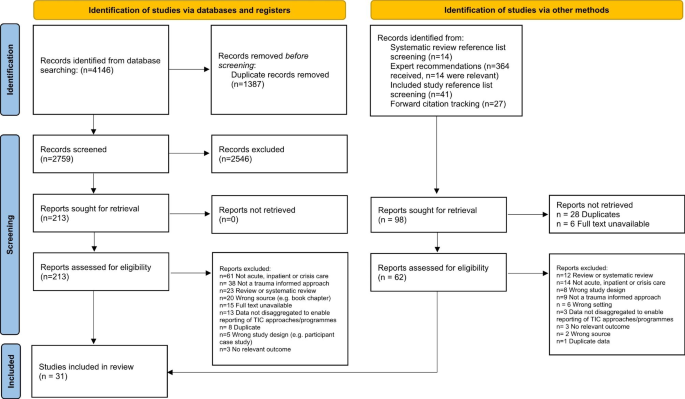

The database search returned 4146 studies from which 2759 potentially relevant full-text studies were identified. Additional search methods identified 96 studies. Overall, 31 studies met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The PRISMA diagram can be seen in Fig. 1. Characteristics of all included studies are shown in Table 1.

PRISMA diagram demonstrating the search strategy. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Study characteristics

The models reported most commonly were the Six Core Strategies (n = 7) and the Sanctuary Model (n = 6). Most included studies were based in the USA (n = 23), followed by the UK (n = 5), Australia (n = 2), and Japan (n = 1). Most studies were undertaken in acute services (n = 16) and residential treatment services (n = 14), while one was undertaken in an NHS crisis house. Over a third of studies were based in child, adolescent, or youth mental health settings (n = 12), while six were based in women’s only services. See Table 1 for the characteristics of all included studies.

Twenty-one studies gave no information about how they defined ‘trauma’ within their models. Of the ten studies that did provide a definition, four [51,52,53,54] referred to definitions from a professional body [5, 55, 56]; three studies [57,58,59] used definitions from peer-reviewed papers or academic texts [60,61,62,63]; in two studies [64, 65], authors created their own definitions of trauma; and in one study [66], the trauma definition was derived from the TIC model manual. See full definitions in Appendix 3. Some studies reported details on participants’ experiences of trauma, these are reported in Table 1.

What trauma informed approaches are used in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Thirty-one studies in twenty-seven different settings described the implementation of trauma informed approaches at an organisational level in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential settings. The different models illustrate that the implementation of trauma informed approaches is a dynamic and evolving process which can be adapted for a variety of contexts and settings.

Trauma informed approaches are described by model category and by setting. Child and adolescent only settings are reported separately. Full descriptions of the trauma informed approaches can be seen in Appendix 3. Summaries of results are presented; full results can be seen in Appendix 4.

Six Core Strategies

Seven studies conducted in four different settings implemented the Six Core Strategies model of TIC practice for inpatient care [51, 59, 65, 67,68,69,70]. The Six Core Strategies were developed with the aim of reducing seclusion and restraint in a trauma informed way [71]. The underpinning theoretical framework for the Six Core Strategies is based on trauma-informed and strengths-based care with the focus on primary prevention principles.

Inpatient settings: child and adolescent services

Four studies using Six Core Strategies were conducted in two child and adolescent inpatient settings using pre/post study designs [59, 67,68,69]. Hale (2020) [67] describes the entire process of implementing the intervention over a 6-month period and establishing a culture change by 12 months, while Azeem et al’s (2015) [69] service evaluation documents the process of implementing the six strategies on a paediatric ward in the USA over the course of ten years.

Inpatient settings: adult services

Two studies focused on the use of the Six Core Strategies in adult inpatient and acute settings [51, 65]. One further study, Duxbury (2019) [70], adapted the Six Core Strategies for the UK context and developed ‘REsTRAIN YOURSELF’, described as a trauma informed, restraint reduction programme, which was implemented in a non-randomised controlled trial design across fourteen adult acute and inpatient wards in seven hospitals in the UK.

How does the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Five studies, only one of which had a control group [70], reported a reduction in restraint and seclusion practices after the implementation of the Six Core Strategies [59, 67,68,69,70]. Two studies [51, 65] did not report restraint and seclusion data.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff reported an increased sense of pride in their ability to help people with a background of trauma [59], which came with the skills and knowledge development provided [51]. Staff also showed greater empathy and respect towards service users [51, 65].

Staff recognised the need for flexibility in implementing the Six Core Strategies, and felt equipped to do this; as a result they reported feeling more fulfilled as practitioners [51]. Staff shifted their perspectives on service users and improved connection with them by viewing them through a trauma lens [65]. Staff also reported improved team cohesion through the process of adopting the Six Core Strategies approach [51]. It was emphasised that to create a safe environment, role modelling by staff was required [65].

How does the Six Core Strategies impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Service users were reportedly more involved in their own care; they reviewed safety plans with staff, and were involved in their treatment planning, including decisions on medication [51, 65]. Staff and service users also engaged in shared skill and knowledge building by sharing information, support, and resources on healthy coping, and trauma informed care generally [51, 65]. Staff adapted their responses to service user distress and adopted new ways of managing risk and de-escalating without using coercive practices [51, 59]. Finally, service user-staff relationships were cultivated through a culture of shared learning, understanding, and trust [65].

How does the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported a reduction in the duration of hospital admission [59], which was largely attributed to the reduction in the amount of documentation that staff had to complete following crisis interventions.

The Sanctuary Model

Six studies, referring to five different settings [57, 58, 72,73,74,75], employed the ‘Sanctuary Model’ [76] as a TIC model of clinical and organisational change. One further study [72] combined the ‘Sanctuary Model’ with ‘Seeking Safety’, an integrated treatment programme for substance misuse and trauma. All studies were conducted in child and adolescent residential emotional and behavioural health settings in the USA.

The Sanctuary Model is a ‘blueprint for clinical and organisational change which, at its core, promotes safety and recovery from adversity through the active creation of a trauma-informed community’ [76]. It was developed for adult trauma survivors in short term inpatient treatment settings and has formally been adapted for a variety of settings including adolescent residential treatment programmes. No studies explored the use of the Sanctuary Model as a TIC approach in adult inpatient or acute settings, and no studies specifically tested the efficacy of The Sanctuary Model in child and adolescent settings. Studies employing the Sanctuary Model used a range of designs including longitudinal, qualitative methods, service evaluations/descriptions and a non-randomised controlled design.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

In a service description, Kramer (2016) [57] reported that service users experienced clear interpersonal boundaries with staff, facilitated by healthy attachments and organisational culture. Service users also experienced staff responses as less punitive and judgemental.

How does the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Kramer (2016) [57] described decreasing rates of absconscion, restraint, and removal of service users from the programme post-implementation of the Sanctuary Model, which the authors hypothesised was due to the safe environment, and the movement towards a culture of hope.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

Staff received the Sanctuary Model positively [72, 73] and it gave them a sense of hopefulness [75]. However, it was widely acknowledged that it was resource intensive for staff to implement TIC in practice and additional training may be needed [73].

Korchmaros et al. (2021) [72] reported that the Sanctuary Model components most likely to be adopted were those that staff found most intuitive, though staff generally did not believe the model was acceptable in its entirety for their clinical setting. As staff communication improved, so did physical safety for staff and service users, and team meeting quality [75]. Staff appreciated the improved safety – or perception of such – after implementing the Sanctuary Model [73, 75].

Staff reported that the Sanctuary Model promoted a healthy organisational culture with a commitment to a culture of social responsibility, social learning [57] and mutual respect [73].

How does the Sanctuary Model impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

Following implementation, staff focused more on service user recovery through teaching service users adaptive ways of coping and encouraging empathy and compassion towards service users [58, 73, 75]. Staff reported a holistic and compassionate understanding of the associations between trauma, adversity and service user behaviour [73]. Staff also reported sharing more decisions with service users [73] and collaboratively involving service users in their treatment care, safety plans, and in the development of community rules [73, 75]. Staff felt able to communicate information, ideas, and their mistakes more openly, and their ability to model healthy relationships was seen as a fundamental to treatment [75].

How does the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported a reduction in staff compensation claims due to a reduction in harms from physical interventions [72].

Comprehensive tailored trauma informed model

We categorised eight models [52, 53, 77,78,79,80,81,82] as ‘comprehensive tailored TIC models’. This reflects models that are holistic and multi-faceted, but do not closely follow an established TIC intervention model or blueprint and have instead been developed locally or to specifically complement the needs of a specific setting.

Residential settings: child and adolescent services

Three studies describe comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in child and adolescent residential treatment settings [77,78,79]. At an organisational level, key features of the tailored approaches include whole staff training using a trauma informed curriculum [77,78,79], creating a supportive, therapeutic environment and sense of community, using a family-centred approach, structured programmes of psychoeducational, social and skills groups [77, 79] and collaborative working across different agencies [78, 79].

Residential settings: adult women-only substance misuse service

Three studies [53, 80, 81] describe a gender-specific trauma informed treatment approach in a female only environment. Key components include providing training for all staff on trauma and trauma informed approaches, team support and supervision from a trained trauma therapist, social and life skills groups [53]; individual therapy and family support programme [81]; trauma informed group therapies and psychoeducation [53, 80]; the implementation of a ‘gender specific, strengths based, non-confrontational, safe nurturing environment’ and strategic level meetings to identify structural barriers and gaps across different agencies [80]. Zweben et al. (2017) [81] focused specifically on family-centred treatment for women with severe drug and alcohol problems.

Inpatient settings: adults and children/adolescents

The ‘Patient Focussed Intervention Model’ [82] was implemented in a variety of settings including residential child and adolescent, adult acute and adult longer term inpatient stays. This model was developed using a collaborative process with involvement from service users, staff, administrators, and external collaborators with continuous quality improvement. The model incorporated (i) an individual TIC treatment model, which emphasised a patient-centred approach to building a culture and environment which is soothing and healing (e.g., by making changes to the physical environment and providing animal assisted therapy), (ii) the Sorensen and Wilder Associates (SWA) aggression management program [83] and (iii) staff debriefing after incidents of aggression.

Inpatient settings: women-only forensic service

Stamatopoulou (2019) [52] used qualitative research methods to explore the process of transitioning to a TIC model in a female forensic mental health unit [52] using the ‘trauma informed organisational change model’ [84]. Components included (i) staff training on trauma-informed care, (ii) co-produced safety planning through five sessions of Cognitive Analytic Therapy [85], (iii) a daily ‘Trauma Champion’ role for staff, and (iv) reflective practice groups for staff and service users.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In a study by Tompkins & Neale (2018) [53], service users reported being unaware that the service they were attending was trauma informed and were therefore not anticipating being encouraged to confront and reflect on their traumas [53]. However, the daily structure and routine timetable created a secure environment for their treatment experience. Service users who remained engaged with the service felt cared for by staff, and that the homely atmosphere in the service supported them to feel secure.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Three studies reported data on seclusion and restraints; all indicated a decrease [78, 81, 82]. Brown et al. (2013) [78] quantitatively reported reductions in the use of both seclusion and restraint in the year following Trauma Systems Therapy implementation, and the reduction in use of physical restraints was significant and sustained over the following eight years. Goetz et al. (2012) [82] also quantitatively reported that seclusion and restraint rates halved following implementation of the Patient Focused Intervention Model, as well as reductions in: (i) staff injuries, (ii) hours in seclusion and restraint and (iii) the number of aggressive patient events. However, while the number of seclusion room placements was lower, the average number of restraints among children and young people was higher in TIC compared to usual care.

Using a pre-post design, Zweben et al. (2017) [81] reported that service users receiving TIC reported fewer psychological and emotional problems after a month, compared to on entry to the programme, as well as reduced drug and alcohol misuse. Service user average length of stay was higher among those in the programme, compared to those not enrolled. Finally, as court and protective services became aware of the service users’ improvements, reunifications with children approached 100%.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Two papers reported on staff attitudes and experiences [52, 53]. Some staff experienced introduction of TIC as overwhelming, leaving them unsure about what was expected from them throughout the training and implementation process, and that it might have been more successful had it been implemented in stages [52]. Some staff also felt unsure of what TIC entailed even after training, and it took time for staff to feel competent and confident [53]. Staff who had the least awareness of TIC experienced the greatest change anxiety when they were told of its implementation. When there were conflicting views within the team, the consistency of implementation was reduced [52]. Conversely, however, staff reported a sense of achievement in having implemented TIC and consequently an increased sense of job satisfaction.

Staff reported that their own traumatic experiences can inform the way they communicate and react to situations in the clinical environment, and they needed help to set boundaries and avoid emotional over involvement [53]. Implementing TIC broke down barriers between their private and professional selves, and there was an increased awareness of the personal impact of their work.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Stamatopoulou (2019) [52] reported that with the introduction of TIC, staff moved away from a solely diagnosis-based understanding of distress and developed an ability to formulate connections between service users’ backgrounds and their clinical presentations. As a result, staff showed empathy and respect towards service users and approached sensitive situations with service users more mindfully. Staff adopted new ways of managing risk [52] and service users were collaboratively involved in the development of treatment care plans [53]. Goetz et al. (2012) [82] also reported reduced staff injuries in the first year after implementing TIC.

There was an increased focus on staff wellbeing as well as greater awareness of staff personal boundaries and experiences of trauma and adversity, which led to staff feeling as though they had more in common with service users than expected [52]. Staff also discussed the importance of protecting their wellbeing by maintaining personal and professional boundaries, practicing mindfulness, and attending mutual aid groups [53].

Wider group relationships were reportedly redefined, and the impact of the work on staff wellbeing was acknowledged, specifically the ways in which staff’s own trauma informed their reactions to incidents on the ward [52]. Staff reported a greater sense of team connectedness, and that their individual professional identities were reconstructed.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

Staff had concerns over the sustainability of the model, especially in an organisation that could not offer the time or money required for service development [52]. Fidelity to a model varied depending on which staff were working; for instance, when agency staff or new joiners were working, fidelity was low and crisis incidents increased.

Adolescents in residential treatment receiving TIC spent significantly less time in treatment compared to those receiving traditional treatment, with the receipt of trauma informed psychiatric residential treatment (TI-PRT) accounting for 25% of the variance in length of stay [77]. Similarly, authors observed reduced length of hospital admissions after the introduction of their TIC approach [79].

Safety focused tailored trauma informed models

Two studies [86, 87] tailored their own trauma-informed approach to create a culture of safety and (i) reduce restrictive practices and (ii) staff injuries. A third study [88] utilised a Trauma and Self Injury (TASI) programme, which was developed in the National High Secure Service for Women.

Inpatient settings: adults and child/adolescent services

Blair et al. (2017) [86] conducted a pilot trauma informed intervention study with the aim of reducing seclusions and restraints in a psychiatric inpatient hospital facility. Intervention components included the use of Broset Violence Checklist (BVC) [89,90,91]; 8-hour staff training in crisis intervention; two-day training in “Risking Connections” [92]; formal reviewing of restraint and seclusion incidents; environmental enhancements; and individualised plans for service users.

Borckardt et al. (2011) [87] reported a ‘trauma informed care engagement model’ to reduce restraint and seclusion across five various inpatient units (acute, child and adolescent, geriatric, general and a substance misuse unit). The intervention components included TIC training, changes in rules and language to be more trauma sensitive, patient involvement in treatment planning and physical changes to the environment.

Inpatient settings: women-only forensic service

Jones (2021) [88] reported the TASI programme in a high security women’s inpatient hospital, which aimed to manage trauma and self-injury with a view to reducing life threatening risks to service users and staff. The programme: (i) promotes understanding of trauma through staff training, staff support and supervision on the wards, (ii) provides psychoeducation and wellbeing groups for service users, (iii) focuses on the improvement of the therapeutic environment, (iv) promotes service users’ ability to cope with their distress, and (v) provides individual and group therapy.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of safety focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In Jones (2021) [88], some women reported feeling initially overwhelmed by and underprepared to acknowledge and work on their trauma experiences, and sometimes felt their distress was misunderstood by the nurses in their setting, which could lead to an escalation [88]. Service users felt connected to themselves, to feel safe and contained, particularly in comparison to previous inpatient experiences. Overall, however, the service did not make the women feel as though their problems were fully understood.

How do safety-focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Reductions in the number of seclusions and restraint were reported [86, 87]. Specifically, the trauma informed change to the physical therapeutic environment was associated with a reduction in the number of both seclusion and restraint [87]. The duration of restraints reportedly increased, while duration of seclusion decreased [86].

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering safety focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In Jones (2021) [88], nurses emphasised that shared understanding and trust were instrumental in connecting and communicating with the women in their service [88]. Nurses also cultivated service user-staff therapeutic relationships, which they experienced as intensely emotional. The nurses reported becoming more critical of other staff members they perceived as lacking compassion towards the service users. Finally, staff felt that a barrier to the nurse-service user relationship was the staff’s inability to share personal information and vulnerability back to the service user.

How do safety focused tailored trauma informed models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff developed new tools and adapted their responses to trauma and distress, and service users were also involved in some, but not all, staff training [88]. There were changes to information sharing practices [52]; information on service users’ history and intervention plans were more openly shared within the team to ensure all staff had the same information and did not need to risk re-traumatising service users by asking for information again. Service users also reported being more involved in their treatment planning [51, 87] and medication decisions [65].

Trauma informed training intervention

Three studies focused on trauma informed training interventions for staff [66, 93, 94]. All studies used a pre/post design to evaluate effectiveness.

Residential settings: child and adolescent services

Gonshak (2011) [66] reported on a specific trauma informed training programme called Risking Connections [92] implemented in a residential treatment centre for children with ‘severe emotional disabilities’. Risking Connections is a training curriculum for working with survivors of childhood abuse and includes (i) an overarching theoretical framework to guide work with trauma and abuse (ii) specific intervention techniques (iii) a focus on the needs of trauma workers as well as those of their clients.

Inpatient settings: adult services

Niimura (2019) [93] reported a 1-day TIC training intervention, covering items including the definition of trauma, evidence on trauma and behavioural, social, and emotional responses to traumatic events, on attitudes of staff in a psychiatric hospital setting. Aremu (2018) [94] reported a training intervention to improve staff engagement which they identified as a key component of TIC. The intervention was a 2-hour training on engaging with patients, however the specific content of the training is not specified.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering trauma informed training interventions in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Following training, half of staff reported feeling their skills or experience were too limited to implement changes and also that staff experienced difficulties when trying to share the principles of trauma informed care with untrained staff [93]. However, TIC training did produce positive attitude shifts towards TIC.

How do trauma informed training interventions impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff modified their communication with service users by altering their tone and volume, and adopted new ways of managing risk without using coercive practices [93]. There was also a reported a reduction in the use of as-needed medication [94].

How do trauma informed training interventions in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported that educating staff about TIC in residential settings was time intensive and may require frequent or intense “booster” sessions following the initial training [66]. In terms of evaluation, it took time to implement TIC in the residential setting and then to collect related outcome data.

Other TIC models

This category reports studies which have made attempts to shift the culture towards trauma-informed approaches but have not made full-scale clinical and organisational changes to deliver a comprehensive trauma informed model [28, 54, 64, 95].

Inpatient settings: adult services

Isobel and Edwards’ (2017) [64] case study on an Australian inpatient acute ward described TIC ‘as a nursing model of care in acute inpatient care’. This intervention was specifically targeted at nurses working on acute inpatient units but did not involve members of the multi-disciplinary team.

Beckett (2017) [95] conducted a TIC improvement project on an acute inpatient ward (which primarily received admissions through the hospital emergency department) using workforce development and a participatory methodology. Staff devised workshops on trauma informed approaches, through which six key practice areas were identified for improvement by the staff team.

Jacobowitz et al. (2015) [54] conducted a cross-sectional study in acute psychiatric inpatient wards to assess the association between TIC meetings and staff PTSD symptoms, resilience to stress, and compassion fatigue. Neither the content nor the structure of the ‘trauma informed care meetings’ were described in further detail.

Crisis house setting

Prytherch, Cooke & March’s (2020) [28] qualitative study of a ‘trauma informed crisis house’, based in the UK, gives a partial description of how trauma informed approaches were embedded in the service delivery and design.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Prytherch, Cooke and March (2020) [28] reported that their TIC model created a positive experience for service users by making them feel worthwhile, respected and heard by staff [28]. Service users valued being trusted by staff, for example, to have their own room keys and to maintain their social and occupational roles, which were a key source of self-worth. While service user experiences were often positive, they found being asked directly about trauma challenging. This was invalidating for those who did not initially identify as having experienced trauma. Some service users also felt the TIC programme could only support them so far, as it did not incorporate or address wider societal injustices, such as issues related to housing and benefits, that can contribute to and exacerbate distress.

How do other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Beckett et al. (2017) [95] reported that in the three years after the TIC workshops, rates of seclusion dropped by 80%, as did the length of time spent in seclusion, with most seclusions lasting less than an hour.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff found an increased sense of confidence and motivation in managing emotional distress and behavioural disturbance [95]. Staff also showed increased respect, understanding and compassion towards service users.

Similarly, staff expressed hope for improved care in future, on the basis that they were better skilled to deliver care that was consistent and cohesive, while also being individual and flexible [64]. They reported a need for clarity and consistency in their role expectations and felt that changes in practice needed to be introduced slowly and framed positively. Conversely, others felt the changes introduced were too minimal to be significant and did not much vary from existing practice. Some staff expressed a fear of reduced safety that could follow changes to longstanding practice. Ambivalence to change stemmed from different degrees of understanding of TIC among staff, and others felt personally criticised by the newly introduced approach, specifically that their previous practice had been labelled traumatising.

How do other TIC models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Some staff modified their communication with service users, e.g., reducing clinical jargon and focusing on the strengths of the service users [95]. Regular opportunities for service users and staff to discuss and reflect on information, concerns, and experiences were established. Staff received training in physical safety and de-escalation procedures; subsequently, the need for security staff on the ward decreased. Finally, in terms of staff wellbeing, staff PTSD symptoms increased with an increase in signs of burnout and length of time between attending trauma-informed care meetings [54].

link

More Stories

Recovery-oriented and trauma-informed care for people with mental disorders to promote human rights and quality of mental health care: a scoping review | BMC Psychiatry

Best Healthcare Destinations for AI-Powered Post-Trauma Recovery | Medical Tourism Magazine | Medical Travel

New Study Examines Patient Suicide and Its Toll on Providers